Copyright © 2008 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 54, No 4 - Winter 2008

Editor of this issue: M. G. Salvėnas

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2008 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 54, No 4 - Winter 2008 Editor of this issue: M. G. Salvėnas |

The Lithuanian Language in the United States: Shift or Maintenance?

Aurelija Tamošiūnaitė

Aurelija Tamošiūnaitė is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Slavic & Baltic Languages and Literatures at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her areas of scholarly interest are sociolinguistic history of the Lithuanian language, history of standard languages, sociolinguistics, and Lithuanian language in the U.S.

Abstract

According to United States Census data (2000), there were 38,295 people

in the United States that speak Lithuanian. Almost 90 percent of

Lithuanian speakers in the U.S. declared that they speak English

„very well“ or „well“, and only

10 percent – „not well“ or „not

at all“. Thus data significantly point to a language shift

from Lithuanian to English among Lithuanian speakers in the U.S. Since

there are only a few studies conducted on Lithuanian language in the

U.S. or studies that investigate generational language shift among

Lithuanian speakers, but there is no reliable evidence to confirm the

shift of language or generational loss. In this article signs of shift

and maintenance among Lithuanian speakers, based on a study conducted

in two Chicago-area Lithuanian Saturday schools (in Gage Park and

Lemont), using self-report questionnaires, are presented with

conclusions.

Introduction

According to the United States Census data, in 2000 there were almost 660,000 people of Lithuanian descent living in the United States. Compared to other ethnicities, Lithuanian is a very small ethnic group, forming only 0.2 percent of the total U.S. population. In addition, of the 660,000 Lithuanian-descent Americans, the 2000 census shows only 38,295 Lithuanian speakers. This indicates that only 5.8 percent of people declaring Lithuanian ancestry actually speak Lithuanian. Although this number is small, one should keep in mind that the entire population of Lithuania consists of just over 3 million people, according to the Department of Statistics of the Republic of Lithuania. This is almost ten times less than the number of Spanish speakers living in the U.S. (35.3 million, 2000 United States Census).

Between 1990 and 2000, the number of Lithuanian speakers in the U.S. population decreased by 10 percent, from 0.024 to 0.014. Despite the fact that there are more people declaring their Lithuanian ancestry (the 1990 census indicates 526,089 people with Lithuanian descent, the 2000 census – 659,992), the number of speakers is diminishing: in 1990 there were 55,781 Lithuanian speakers, while the 2000 census counts only 38,295 of them. In the 2000 census, almost 90 percent of Lithuanian speakers in U.S .declared they spoke English “very well” or “well”, and only 10 percent – “not well” or “not at all”. Thus the data points to a significant language shift from Lithuanian to English among Lithuanian speakers in the U.S. Since there are almost no studies done on Lithuanian language maintenance in the U.S., nor any studies investigating generational language shift among Lithuanian speakers, there is no reliable evidence to confirm the shift of language or generational loss. Therefore in this paper I will try to present the signs of maintenance or shift in the usage of Lithuanian and English, based on a study conducted in October 2007 in two Chicago-area Lithuanian Saturday schools.

Overview of sociolinguistic literature on American Lithuanian

There are only a few studies done on American Lithuanian. In several articles Lionginas Pažūsis (1973, 1988) focused more on lexical (English semantic loans) and phonological differences (the distinction between hard and soft consonants among American Lithuanians, as well as aspiration at the word initial position that is not common for Standard Lithuanian, etc.) between Standard Lithuanian and American Lithuanian. However, other sociolinguistic issues were not addressed in his studies.

In her dissertation, Jolanta Macevičiūtė (2000) focused on the loss of the distinction between registers in American Lithuanian and Full Lithuanian, as she named “the language variety spoken natively by its speech community in the Republic of Lithuania” (Macevičiūtė 2000, 4). According to her observations, Lithuanian language among American Lithuanians is used only in some registers of speech, mostly in those that are related to home, family or any Lithuanian community issues. Any change in topic during the conversation (e.g., to business) usually signals a switch to English. (Macevičiūtė 2000, 23).

She analyzed two types of registers: written and spoken, for both American Lithuanian and Full Lithuanian. American Lithuanian data represents second-generation speakers, born in the U.S. to parents of the post-World War II immigration. 62 One of the main observations between the first (G1) and second (G2) generation speakers she made is that G2 usually do not command the written register of Lithuanian. Another observation, related to the lexico-grammatical level, is the loss of the genitive in negation; accusative is used instead. Due to language contact, there are a number of English borrowings that usually take the Lithuanian suffixes and endings in order to conform to the rules of Lithuanian language morphology. Direct translations of some terms whose equivalents are not known to American Lithuanian speakers (2000, 32–35), as well as some differences in sentence structure, such as loss of word order variation and a decrease in object fronting construction, were observed (2000, 86). However, the issue of the third generation (G3), and the loss or maintenance of the language in this generation, is not addressed in her dissertation.

A study by Algis Norvilas on language choice among young Lithuanian bilinguals (1990), although it was done within the framework of phenomenological psychology, provides us with useful data on the usage of Lithuanian in the U.S. In this study, Norvilas interviewed 19 women and 20 men, giving them questionnaires asking why, when, under what circumstances, and what language do they use when speaking to a young Lithuanian who is bilingual. The average age of the respondents was 18–19 years; all of respondents lived in the vicinity of Chicago, Illinois; all of them were G2 speakers, i.e., the children of the second wave immigrants; almost all of them were graduate students, belonged to Lithuanian organizations; and all “identified Lithuanian as the first language they had learned” (Norvilas 1990, 218). However, the majority of respondents felt more comfortable speaking English. The ability to speak and understand Lithuanian was higher than the ability to read and write. Most of the respondents indicated that they used Lithuanian more with their parents; whereas, with their siblings or friends they tended to use English more (Norvilas 1990, 218). Thus, this points very clearly to a shift to English.

The results of the research provided not only demonstrated the choice between languages, but also revealed different at63 titudes toward English and Lithuanian as well. English usually was considered “natural” and “automatic”, while Lithuanian was marked by a sense of a lack of proficiency. If Lithuanian was associated with positive feelings such as pride, English did not have any sentiments attached to it (Norvilas 1990, 222). Usually English is preferred in these situations: when meeting a person for the first time, when the person’s ability to speak Lithuanian is not strong, when an American (third party) is present in the conversation, at the University, and when the speaker himself feels his knowledge of Lithuanian is limited. Lithuanian is preferred: with close friends, with someone who starts speaking Lithuanian first, with someone who is fluent in Lithuanian, with older people (out of respect for them), at Saturday school (and other Lithuanian organizations or places), when they do not want to be understood by others (English speakers).

The study by Norvilas (1990) is important because it shows clearly the signs of language shift toward English among G2 Lithuanian bilinguals. The division between language choice toward older people and peers is especially important here, as well as the fact that almost all respondents stressed the “naturalness” of English, as the language that is easier to speak and to think in. This fact indicates that the natural choice between languages is much more in favor of English than Lithuanian. However, this study was conducted in the early 1990s and does not provide data on the third generation (G3).

The case of two Chicago-area Lithuanian Saturday schools methodology and data

This study comparing attitudes toward the Lithuanian language and the choice of Lithuanian and English among teenage American Lithuanian speakers was conducted in two Lithuanian Saturday schools. One school, the Chicago Lithuanian School, is located in the city of Chicago, and the other, Maironis Lithuanian School, is located in Lemont, one of the southwestern suburbs of Chicago with a high concentration of Lithuanians. One of the reasons why these two schools were 64 chosen was the high number of schoolchildren attending these schools. During the 2006–2007 school year, there were 320 students in the Chicago Lithuanian School and 493 students in the Lemont-based school (figures provided by the Lithuanian Educational Council of the USA). Another reason why these two schools were chosen is because of the different immigration patterns they represent. In the Chicago Lithuanian School, most of the students are the children of recent immigrants (third wave) from Lithuania, thus, most of them were born in Lithuania, i. e. they are G1 and G1.5 speakers.1 In contrast, the background of the students in Lemont is much more diverse: the representatives of all three generations can be found here (G1, G1.5, G2, G3).

Since the purpose of this research was also to compare the results with those of Norvilas (1990), only the students from the highest grades (8, 9, 10) in both schools were interviewed. Self-report questionnaires were given to the students in each school. The questionnaire was created using Norvilas’s data (1990) as well as the sample of a similar study conducted by Potowski with Spanish college students in Chicago (Potowski 2004). The questionnaire consists of three parts. The first part of the questionnaire provides the basic sociological information about the respondent (age, sex, place [country] of birth, etc.) In the second part, the students are asked to fill in two tables with an approximate percentage of their usage of Lithuanian and English with their parents, brothers/sisters (i.e. people they live with at home) as well as grandparents, aunts, and cousins. Several questions on language choice with multiple choice answers are also provided in this part. In the third part of the questionnaire, students provided information on their parents’ place of birth (to find out what generation of Lithuanian speakers they belong to) and evaluated their knowledge of English and Lithuanian.

Students (Respondents)

The questionnaire was completed by 82 (42 female and 40 male) students. 45 students were from the Chicago Lithuanian School, and 37 from Maironis Lithuanian School in Lemont. The average age of the respondents was 14.2 years. 76 percent (62) of all respondents were born in Lithuania, and 24 percent (20) in the U.S. From those who were born in the U.S. almost 80 percent of their parents were born in the U.S., the remaining 20 percent were born in Lithuania, and one father was born in Germany. Of those who were born in Lithuania, the age at arrival is given in Table 1.

Table 1: Respondents’ age at arrival

|

Age

at arrival |

||||

|

Before

3 |

3–5 |

5–10 |

Over

10 |

Total |

|

0% |

21% |

51% |

28% |

100% |

Table 2: Number of years in the U. S.

|

Number of years |

||||

|

Less than |

3–8 |

8–12 |

Over 12 |

Total |

|

14% |

52% |

32% |

2% |

100% |

The different pattern of generations in the two Chicago area schools is given in Table 3.

Table

3: Respondents by generation in two Chicago area

Lithuanian Saturday schools

|

|

|

Both

|

||

|

Generation |

Number

of respondents |

Generation

|

Number

of respondents |

Total

number of respondents |

|

G1 |

9 |

G1 |

3 |

12 |

|

G1.5 |

27 |

G1,5 |

11 |

38 |

|

G2 |

8 |

G2 |

8 |

16 |

|

G3 |

1 |

G3 |

15 |

16 |

|

Total |

45 |

Total |

37 |

82 |

Findings

Students had to provide the percentage of their use of Lithuanian and English to and from parents, siblings, grandparents, and other relatives or friends. The usage of Lithuanian language twhen speaking to parents is given in Table 4.

Table 4: Percent of Lithuanian language use to/from parents

|

No.

of years |

To |

From

mother |

To |

From |

To |

From |

|

Fewer

than 3 (9) |

99.20% |

99.40% |

99.14% |

100.00% |

99.18% |

99.68% |

|

3

to 8 (33) |

97.12% |

98.54% |

99.34% |

99.51% |

98.23% |

99.03% |

|

8

to 12 (19) |

95.20% |

98.60% |

95.90% |

98.90% |

95.58% |

98.76% |

|

Over

12 (21) |

73% |

77% |

79.60% |

78.70% |

76.33% |

78.00% |

|

Average

(82) |

91.13% |

93.39% |

93.50% |

94.28% |

92.33% |

93.87% |

With siblings

Table 5: Percent of Lithuanian spoken to/from siblings

|

Amount

of time |

To |

From |

To |

From |

To |

From |

|

Fewer

than 3 (9) |

90% |

90% |

99.20% |

98.80% |

97.66% |

97.33% |

|

3

to 8 (33) |

96.11% |

89.78% |

96.87% |

95.50% |

96.34% |

90.59% |

|

8

to 12 (19) |

90% |

83.70% |

75.60% |

81.80% |

88.73% |

82.94% |

|

Over

12 (21) |

59.90% |

57.90% |

62.10% |

60.20% |

60.80% |

77.83% |

|

Average

(82) |

84% |

80% |

83.44% |

84.08% |

85.88% |

87.17% |

Table 6: Percent of Lithuanian to/from parents and to/from siblings

|

Amount of time |

To |

From |

To |

From |

|

Fewer than 3 (9) |

99.18% |

99.68% |

97.66% |

97.33% |

|

3 to 8 (33) |

98.23% |

99.03% |

96.34% |

90.59% |

|

8 to 12 (19) |

95.58% |

98.76% |

88.73% |

82.94% |

|

Over 12 (21) |

76.33% |

78.00% |

60.80% |

77.83% |

|

Average (82) |

92.33% |

93.87% |

85.88% |

87.17% |

Other relatives

Table 7:

Percent of Lithuanian

use to/from other relatives

|

Amount

of time |

To |

From |

To |

From |

To |

From

|

|

Fewer

than 3 (9) |

93.33% |

90% |

99.80% |

99.80% |

99% |

100% |

|

3

to 8 (33) |

95.80% |

85.30% |

99.93% |

99.94% |

100% |

99.25% |

|

8

to 12 (19) |

40% |

52.50% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

Over

12 (21) |

50.70% |

51.40% |

51.80% |

43.10% |

91% |

92% |

|

Average

(82) |

69.96% |

70% |

87.88% |

85.71% |

98% |

98% |

Lithuanian use with other relatives is similar to that of parents and siblings, in the respect that the use is higher when the addressed person is older. The highest percentage of Lithuanian language use is with grandparents (average 98%), it diminishes when speaking to an aunt or uncle (87.88%), and is the lowest when speaking to cousins (69.96%). The decrease in the use of Lithuanian to cousins is the highest for respondents who have spent more than 8 years in the U. S. Usually cousins are close in age to that of respondents or their siblings; therefore, this decrease in Lithuanian use points to a shift to English.

Language attitudes and language choice

As mentioned earlier, Norvilas investigated language choice between bilingual Lithuanians. Since one of the goals of the present study was to compare language attitudes and use in Chicago-area schools to Norvilas’s findings, the data represented below in Table 11 will show the language choice among respondents, i. e., when and why they prefer to speak Lithuanian or English.

Table 8: Language choice among respondents in two settings

|

|

When you meet a

Lithuanian friend |

What language do

you speak in |

||||

|

Amount of |

Lithuanian |

English |

Both |

Lithuanian |

English |

Both |

|

Fewer

than 3 (9) |

100% |

0% |

0% |

88.88% |

0% |

11.11% |

|

3 to 8 (33) |

51.51% |

3.03% |

45.45% |

63.63% |

6.06% |

30.30% |

|

8 to 12 (19) |

36.84% |

21.05% |

42.10% |

47.36% |

21.05% |

31.57% |

|

Over 12 (21) |

9.52% |

19.04% |

71.42% |

9.52% |

38.09% |

52.8% |

|

Average |

49% |

11% |

40% |

52.35% |

16% |

31.34 |

Norvilas did not provide statistical data on language choice (how many students named one or another reason) in his study, since the questions for the respondents were given in open form. However, his research was useful for the present study, since the answers provided by his respondents were used as multiple choice selections in the questionnaire. Table 12 represents the data on the conditions that influence the language choice among Lithuanians in the present study.

Table 9: Conditions for using Lithuanian

|

What are the

conditions under which you prefer to speak Lithuanian? |

Because it is

easier to express your thoughts |

Because the

person you are talking to does not know English |

Because the

person you are talking to does not have a sufficient knowledge of

English |

Because your

knowledge of English is insufficient |

|

Fewer than 3 (9) |

100% |

22.22% |

33.33% |

22.22% |

|

3 to 8 (33) |

66.66% |

45.45% |

48.48% |

6.06% |

|

8 to 12 (19) |

57.89% |

57.89% |

68.42% |

0% |

|

Over 12 (21) |

19.04% |

71.42% |

76.19% |

9.52% |

|

Average |

61% |

49.25% |

56.61% |

9.45% |

Table 10: Conditions for preferring English

|

What are the

conditions that you prefer to speak English? |

Because it is

easier to express your thoughts |

Because the

person you are talking to does not know Lithuanian |

Because the

person you are talking to does not have a sufficient knowledge of

Lithuanian |

Because your

knowledge of Lithuanian is insufficient |

|

Fewer than 3 (9) |

22.22% |

44.44% |

44.44% |

0% |

|

3 to 8 (33) |

30.30% |

75.75% |

42.42% |

6.06% |

|

8 to 12 (19) |

63.15% |

78.94% |

42.10% |

15.78% |

|

Over 12 (21) |

95.23% |

80.95% |

71.42% |

19.04% |

|

Average |

52.73% |

70.02% |

50.10% |

10% |

Language in which it is easier to express thoughts

Majority of the respondents that spent less than 8 years in the U. S. indicated that Lithuanian is still the language of their natural choice; i.e. it is easier to think in Lithuanian than in English. However, for half of the respondents that have been in the U.S. for 8 to 12 years the choice was Lithuanian, and for another half – English. Thus, I would argue, that the turning-point or rupture for the shift from Lithuanian to English is between 8 and 12 years of stay in the U.S.

Another multiple choice question respondents were asked to answer was related to the issue of identity; in other words, what are the motivations to learn Lithuanian and whether speaking Lithuanian is part of their Lithuanian identity.

Table 11: Motivation to learn Lithuanian

|

Why do you think

you need to learn Lithuanian ? |

Because this is

the language of your parents |

Because you are

Lithuanian |

Because it is

better to know two languages (Lithuanian and English) than one (English) |

|

Fewer than 3 (9) |

77.77% |

77.77% |

55.55% |

|

3 to 8 (33) |

93.93% |

93.93% |

42.42% |

|

8 to 12 (19) |

78.94% |

94.73% |

78.94% |

|

Over 12 (21) |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

Average |

87.66% |

91.61% |

69.23% |

Language proficiency and language dominance

Table 12 represents the students’ reported language proficiency. There was a significant difference between Lithuanian and English proficiency only for those respondents who came to the U.S. recently. 88 percent of these respondents marked “excellent” for Lithuanian, and 55 percent marked “good” for English. There was no significant difference in other groups, since most of them reported that their knowledge of Lithuanian and English was “very good” or “good”. However, this self-evaluation does not prove the real proficiency of their Lithuanian and English, and a more detailed study should be conducted in order to investigate the respondents’ real proficiency.

Table 12: Self reported language proficiency

|

Lithuanian |

|||||

|

|

Excellent |

Very good |

Good |

Not very good |

Bad |

|

Fewer than 3 (9) |

88.88% |

11.11% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

3 to 8 (33) |

51.51% |

51.51% |

12.12%4 |

0% |

0% |

|

8 to 12 (19) |

21.05% |

47.36% |

30,57%6 |

0% |

0% |

|

Over 12 (21) |

19.04% |

47.36% |

38.09%8 |

0% |

0% |

|

Average |

45.12% |

39.34% |

20% |

0% |

0% |

|

English |

|||||

|

|

Excellent |

Very good |

Good |

Not very good |

Bad |

|

Fewer than 3 (9) |

0% |

33.33% |

55.55%5 |

11.11%1 |

0% |

|

3 to 8 (33) |

27.27% |

51.51% |

18.18%6 |

3.03% |

0% |

|

8 to 12 (19) |

47.36% |

47.36% |

5.26% |

0% |

0% |

|

Over 12 (21) |

57.14% |

38.09% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

Average |

33% |

42.57% |

19.75% |

3.54% |

0% |

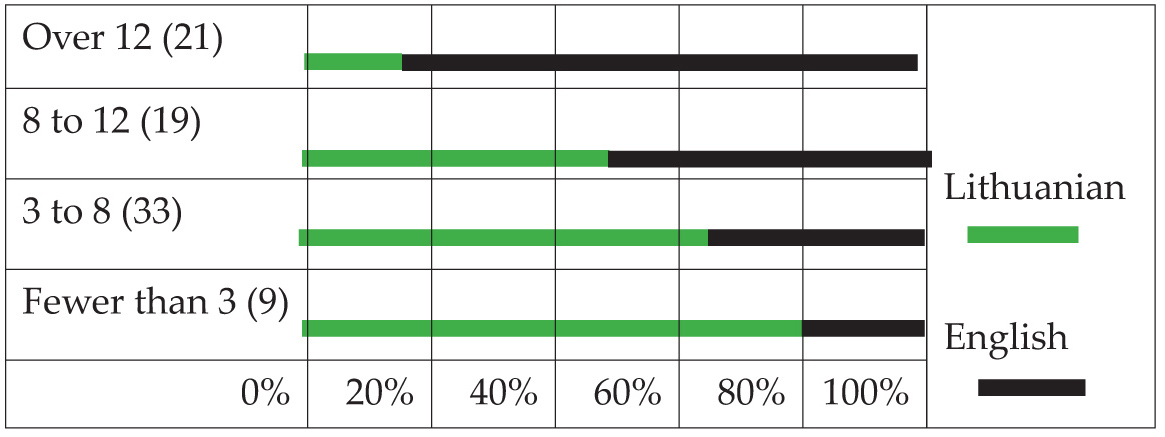

Table 13 below represents self-reported language dominance among respondents. The data again confirms the shift from Lithuanian to English, as well as a correlation between length of stay in the U.S. and diminishing usage of Lithuanian. The table shows nicely how dominant language changes depend on the length of stay in U.S.: for recent immigrants and those who spent 3–8 years in the U.S., Lithuanian is still dominant. For respondents who have spent from 8 to 12 years, the percentage of Lithuanian and English is similar (42%), thus, this could again be the turning-point for the shift from Lithuanian and English among teenage American Lithuanians. No one from the last group reported Lithuanian as their dominant language: 95 percent reported English, and only 5 percent reported the two languages as “equal”. This points significantly to a shift to English, rather than maintenance.

Table 13: Self reported language dominance

|

Which

language do you know better? |

Lithuanian |

English |

Equal |

|

Fewer

than 3 (9) |

88.88%

(8) |

0%

(0) |

11.11%

(1) |

|

3

to 8 (33) |

72.72%

(24) |

21.21%

(7) |

3.03%

(1) |

|

8

to 12 (19) |

47.36%

(9) |

42.10%

(8) |

10.52%

(2) |

|

Over

12 (21) |

0%

(0) |

95.23%

(20) |

4.76%

(1) |

|

Average |

52.24% |

40% |

7.36% |

Conclusion, further research

The data presented in this paper points to a shift from Lithuanian to English among teenage Lithuanian speakers in the U.S. As the study findings point out, there is a correlation between the length of stay in the U. S. and the use of Lithuanian: the longer respondents live in the U. S., the less Lithuanian they use. The turning-point for the shift from Lithuanian to English is indicated to be in the period between 8 to 12 years of stay in the U. S.

The study in two Chicago-area Lithuanian Saturday schools points to the importance of new immigrants. These two schools represent a different generational pattern, since the majority of the respondents in the Chicago Lithuanian School belonged to G1 and G1.5, whereas in the Maironis Lithuanian School, all three generations were represented. However, the small overall number of G3 respondents and the fact that the majority of the students in the Chicago Lithuanian School are G1 and G1.5 indicates that Lithuanian is not mainly maintained intergenerationally; therefore, there is horizontal rather than vertical maintenance of the language. The influx of new immigrants is one of the reasons why Lithuanian is still maintained in the U. S. Thus, recent immigrants help to bolster the use of Lithuanian in the U.S.

Although there are a number of limitations to self-reported questionnaires (e.g., some of the respondents could provide unreliable data because of a desire to please the researcher), however, the percentage of Lithuanian usage was fairly high (even to siblings the average was more than 80 percent). This indicates that Lithuanian, at least among the respondents of this study, is still highly used and maintained.

The data of this study confirmed some of Norvilas’s 1990 findings on language choice among G2 Lithuanian bilinguals. Most of the respondents, similarly to Norvilas’s findings, use Lithuanian mainly with grandparents, parents, or with someone who does not speak English or has limited knowledge of it, as well as in Lithuanian settings (more than 50 percent of the respondents pointed out that they speak Lithuanian during recess in Lithuanian Saturday school). Most of Norvilas’s respondents stressed the “naturalness” of English, since it is easier to express their thoughts in English. The present study showed a similar pattern, depending on how long the respondents have been living in the U.S. Lithuanian was the dominant language for recent newcomers, and for those who were born here or spent more than 12 years here, the dominant language is already English. More than 90 percent of these respondents indicated that it is easier to express their thoughts in English. This points significantly to a shift to English.The turning-point for the shift was the period of 8 to 12 years of stay in the U.S.

Since the study conducted for this paper still missed some aspects, further research could investigate whether respondents plan to pass the language on to their children (this will indicate whether they are going to maintain Lithuanian and if yes, under what conditions and why), what their relationship with Lithuania is (are they visiting it, how often, how long do they stay there), do they use Lithuanian internet (do they chat online, do they take part in forums, do they use Lithuanian letters when they use a computer or not), when they read Lithuanian books, newspapers, magazines, listen to Lithuanian pop music, and watch Lithuanian television. A study on Lithuanian-Americans’ proficiency both in English and Lithuanian would also be useful, since from the self-reported data provided in this study their real proficiency remains somewhat unclear.

1. G1 are those individuals that arrived

to the U.S. after 11 years of age, G2 – those who were born

in the U.S. to parents born abroad or those who arrived to the U.S.

before they were five years of age, and G3 are those born to U.S.-born

parents. All those that arrived in the U.S. between age 5 and 11 belong

to G1.5 (following Potowski 2004).

References

Department of Statistics of the Republic of Lithuania (2005). The number of total population for the 3rd quarter of 2007. Accessed October 20, 2007 at http://www.stat.gov.lt/lt/lt/

Macevičiūtė, Jolanta, 2000. The beginnings of language loss in discourse. A study of American Lithuanian. USC dissertation.

Norvilas, Algis, 1990. “Which language shall we speak? Language choice among young Lithuanian bilinguals.” Journal of Baltic Studies, vol. XXI, no. 3, 215-230.

Pažūsis, Lionginas, 1973. “Anglų kalbos semantiniai skoliniai Šiaurės Amerikos lietuvių kalboje.” Kalbotyra, vol. 26, 27-36.

Pažūsis, Lionginas, 1988. “Anglų kalbos interferencija antrosios JAV lietuvių kartos gimtosios kalbos tartyje.” Kalbotyra, vol. 39, no. 1, 70-80.

Potowski, Kim, 2004. “Spanish language shift in Chicago.” Southwest Journal of Linguistics, 23(1), 87-116.

The Lithuanian Educational Council of the USA. Accessed September 27, 2007 at http://www.svietimotaryba.org/lietschools.html U. S. Census Bureau, 2000. Summary File 3. Accessed September 15, 2007 at: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DatasetMainPageServlet?_ds_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U&_program=DEC&_lang=en